How to get into the best grammar school

A friend’s daughter turned 11 years old this year. As such her class cohort has just been subjected to the highs and lows of the 11+/ secondary school application process. For many children this is a very stressful time, albeit nothing compared to the trauma it is for the parents! I am pretty sure from my friend’s discussions that more parents lost sleep than children. At least I hope this is the case as most parents should be protecting their children from the burden of expectation, as feeling a “failure” at 11 years of age can have lasting consequences. The feeling from the school playground banter which can sometimes approach hysteria, would appear to be that it is substantially harder to get your children into a decent secondary school these days than at any other time in history, however I am never sure if every generation feels this (just like every generation of teenagers feel like they invented sex) and justifies it with current concerns (baby boom, “tiger parented” immigrants taking all the places etc.), or if it is actually true. The word on the London street these days is that if you are sending your child to a state primary school, they have “No chance” of getting into a selective grammar or independent school, unless they are receiving private tuition from at least the beginning of year 4. I have even heard some say that they need tuition from reception, and others say that you need to have their name down with the best tutors at year 1, as they all have mile long waiting lists. If you cannot afford private tuition, then they should be going to Kumon (after school maths club) at least; and the proliferation of Kumon classes across London attest to the power of this notion. If you are sending your children to a prep school, then even they may require private tuition from at least year 4 depending on how your child is doing or the quality of the prep school. If your child is not academically excellent, you could try and sneak them into an academic secondary school by way of a music or drama scholarship, in which case, investment into private music/ drama lessons would have been a requirement from well ahead of year 4, as to audition for a music scholarship at a prestigious school requires a distinction at grade 5 (grade 3 for less prestigious schools). All in all, one wonders about the truth of these rumours or if this is one big ruse to boost the nation’s economy and employment level by increasing consumer spending on “must have” educational add-ons. More worryingly, if this is the truth, then where does it leave children from less well-off families who are unable to afford extra tuition and music lessons?

My eldest child is in year 1, so I am currently in a position to be skeptical about the hysteria. By year 4, Big Sis may well be signed up to the best and most expensive tutor that money can buy to secure her place at “the best selective secondary school in the world ever that is her only salvation from failure, alcoholism, teenage pregnancy and delinquency”. However, from my current armchair standpoint I can only look on with bemusement. I am in the rare position for a Londoner of living in the same area where I spent the majority of my childhood, and having the possibility of my daughter sitting for entrance exams at the same school that I went to: “the best grammar school in London”. Her education and circumstances up to that point will have been somewhat different given my economic circumstances are somewhat better than that of my parents. That said, here is a commentary on how getting into the best grammar school was done in the late 80s.

My sisters and I attended a local state primary school in Wales. My mother, having been a secondary school science teacher in Taiwan, taught us maths after school every day. Since she could not speak English, she did not teach us English but attempted to teach us Chinese. Both my parents encouraged us to read in English and took us to the library to borrow books every Saturday. They also encouraged us to write stories and poems in English. When I was 8 years old, my parents moved to London where both my mother and father had found employment. Since my mother now started working full-time, we had no further additional educational input outside of school, albeit constant encouragement, and expectation of hard work and achievement. My eldest sister was at that important secondary transition stage. Contrary to the at-length planning of most parents these days regarding secondary transfer, my parents, uninitiated in “the system” took a “pitch up and see” attitude. My sister was enrolled directly into the local comprehensive as my parents could not afford private school and she had missed all the entrance exams and procedures for the grammar school. My second sister and I were to go to the local primary which was, and still to this day remains, at the bottom end of the primary school league tables. My eldest sister had many a happy lesson making wooden pencil cases and large clay sculptures of birds of prey, whilst effortlessly coming top in every academic subject. My other older sister and I spent many lessons re-learning how to read and write English with the largely “first language not English” class.

Contrary to the current parental angst over school decisions, my parents took the oft-forgotten-in-current-times view that if it all went a bit Pete Tong, then we could change schools. Within the year, both my sisters had aced entrance exams to the grammar school, one at common entrance, and the other for year 8 entry as a position had opened. I was transferred out of the state primary in our area, to a state primary in the further, but much wealthier suburb next door. How? My parents just applied. Children leave good schools all the time for all sorts of reasons, and if you play the waiting game, chances are you’ll get a place without the furor and hassle of making out that you live on the school’s doorstep at common entrance.

In contrast to my previous school experiences, primary school in leafy suburbia was a delight. Whilst at previous schools my work stood out, in this wealthy neighbourhood intelligent children were in ample supply, such that academic equals and superiors were available. Of the 30 children in my class in this primary school, I know that one other joined me at Cambridge. Another went to Yale and another two went on to study medicine at Oxford and at Bristol, and I am sure there are other successes that I have not heard of. It was my parent’s intention that I should follow in the foot-steps of my sisters into grammar school. Their naivety of the education system meant that they saw this as a foregone conclusion. No tuition was brought in, no music lessons arranged, no past papers ordered up. I remember being called out of class one day by the school’s head of secondary transfer shaking a yellow form at me saying “Your parents have put down a highly selective school as the only option on your secondary transfer form! What if you don’t get in? They must put down alternative options!” To which my genuine response was “But they’ve bought my school uniform already.” I had no idea that entrance heavily depended on my performance, it was just a FACT that this was the school where I was going and I just had to go and sit an exam and attend an interview to formalise the process. Thinking back, this is probably not the best strategy for parents to adopt, as it would have hit me hard if I had not followed my sisters into that school, but my parents were blissfully ignorant of the fierce competition as they were both working flat-out full time and barely spoke to any other parents.

I did nearly blow my chances of going to the grammar school “for Young Ladies” as it was then suffixed. In those days, following the Maths and English paper, you were subjected to an interview with the headmistress. The headmistress was exactly the kind of headmistress I would imagine for a school purporting to educate “Young Ladies”. An upper class lady with portly stature, portent demeanour and penchant for port; all blue rinse and pearls. I had to describe a painting by Braque that was presented to me on a postcard. I had to read aloud a passage of written text about rainfall. It contained the word “percolate”. Here the headmistress requested a definition and I was at a loss. Trying to garner as much information as I could from the surrounding text, I offered a clearly wrong definition. No matter, the headmistress took it upon herself to educate me on the meaning of the word “percolate”. “You know, when you make coffee, you must let the water filter though the spaces between the coffee grounds to get the flavour. You have made coffee before haven’t you?” “Yes” I said. “I put a spoon of the granules into the cup, add hot water and stir. Is that what percolate means?”

Thankfully, being of the Nescafe-drinking classes may have excused my ignorance of the definition of percolate, and I was in. But that was the thing in those days. Raw ability got you through – not primed responses and taught vocabulary.

I am rather saddened to hear that my old grammar school has done away with the interview and rely on an IQ style test to screen candidates prior to entrance exam. On the standard IQ test, there is a 6 point test-retest advantage (this means that purely by having done the test before, the average person can improve their score by almost half a standard deviation). For clinical purposes if you want to get an accurate picture of a child’s IQ you should not test a child more than once a year. If however, you want to inflate your child’s IQ for a one off entrance exam, repeated exposure to IQ type tests can really do it, and schools will not be getting an accurate measure of “intelligence”. I can only imagine that doing away with interviews is a pity as however subjective, I still think there is something to be said for the spark in an eye and a quick-witted response.

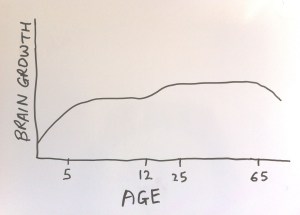

In addition, from my current standpoint, although I value hard work and wish to pass this ethos on to my children, and although I know that hard work can greatly increase a child’s ability and potential, there comes a point where you as a parent have to recognise the innate (genetic) ability of your children, and pushing beyond ability can definitely have negative consequences. We would all like to believe that our child is the brightest bulb in the pack, but all except one of us would be wrong in this assumption. We might all like to believe that if our child “just did this/ or was given this opportunity/ or was helped more by their teacher” that they would become the brightest bulb in the pack, but again, the majority of us would be wrong in this assumption. For some reason, no one seems to want to admit the obvious, that some people are just cleverer than others – no ifs-ands-or-buts about it. Around the school gates, whenever a child’s exceptional reading or maths ability is discussed, someone will inevitably mutter “Yes, but you know what that parent is making the kid do at home…”, whilst my response is always – “great, it really helps everyone to have bright kids in the class”.

My gestalt realisation that ability is unevenly distributed happened at Cambridge University. I looked around me and thought “Not in a million years and working 24/7 will I ever be as smart as some of these people”. Accepting yourself and not feeling a loser about it is really satisfying, and I think we need to have the same reality check sometimes with our kids. Although aspiration and pushing to achieve potential is a positive, not all children have the same academic potential and ultimately we need to accept, appreciate and love them – in the words of Brigitte Jones’s Darcy “just the way they are”. My current view is therefore that if my children do not get into the most prestigious academic school then they probably would not have got on there. I would much prefer my children to perform in the top half of a less academic school, where they can feel “clever” and become confident in their academic abilities than flounder in the bottom half of an academic school. I saw many people at my school and university suffer crises of confidence (despite being exceptionally bright), due to being in the bottom half of a highly academic environment. Some of the negative effects lasted well into adulthood, and may well be life-long. In my view confidence, security, self-assurance and happiness are the solid foundation that childhood needs to build; academic excellence is definitely welcome, but never at the expense of the former.

I am desperately hoping that the rumour mill is hype and that old fashioned clever kids will still end up where they deserve to go and that good education does not become the preserve of the wealthy, but also that I will be strong enough in my current principles to follow through should my children not be “old fashioned clever kids”.