Category: Anxiety

Keep Calm and Carry On: How to Prepare Children for Exam Failure

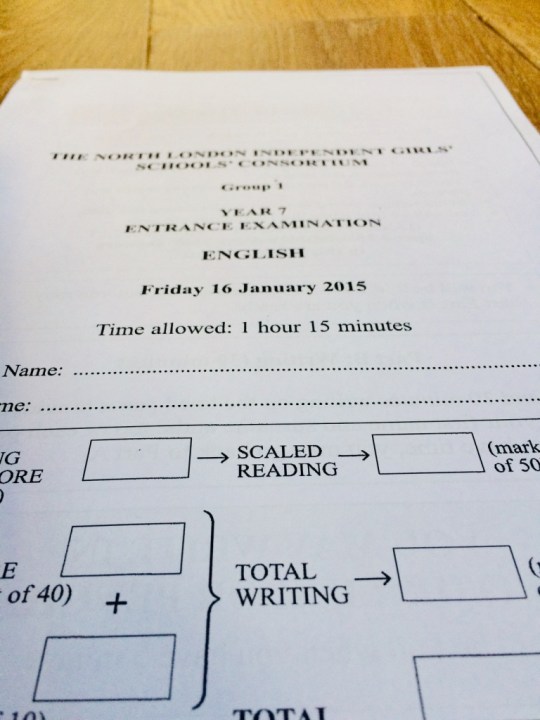

So, Molly is in Year 6 now and I’m sure that I am not the only parent in the anxiety provoking situation of considering secondary transition. I am in the fortunate position (minus a few holidays and luxuries) of being able to consider a private education for my children. This rubs against my preference for all children, from any background, to be able to receive the best possible education, particularly as my siblings and I were all state educated. But where we live in London, in the vicinity of dozens of the top private schools in the country, the difference in available quality of education is all too stark. The draw of these selective schools to the local population, means that many academically able children are removed from the state education system with some demographic consequences for some of the local state schools. While we never considered a private primary education, a private secondary education was always on the cards. Of course, we also applied for the local grammar school for Molly, one that I myself attended in the 80s (see my blog on this), but unfortunately, Molly didn’t make it through the selection process (although I have managed to remain tutor-free). Not altogether surprising since we were told that there were 3500 candidates for 100 places – worse odds (35:1) than Oxbridge (10:1) but still far easier than getting on Love Island (2500:1)! The remaining selective school exam onslaught is in January with weeks required to be cleared from my diary for exams and subsequent interviews and my wallet some-what lighter for the registration fees.

I’m Chinese. I take education seriously. But equally, I am a child psychiatrist and I take mental health even more seriously. Optimal performance in any domain is impaired by poor mental health (as is happiness) and this consideration needs to come first and foremost. When Molly was told that she had not made it through the grammar school exams, she was understandably temporarily disappointed and subdued, but she was readily reassured, and within the hour was back to her usual happy self and has been looking onward and upward. There has been no dent in her self-esteem that I can discern, rather, there has been a smidgeon of increased effort in her work ethic. Given that we have come through and managed the first hurdle of school “rejection” relatively unscathed; I feel somewhat able to advise on some ways that I found useful in combatting rejection dejection.

- Start early and go slow:Adapting to big changes and making a big lifestyle change is always more stressful than making small, incremental changes over time. If you have the long term goal of children sitting selective school exams, I would always advise starting early with a small amount of work (30 minutes a day) up to Year 5 and building incrementally to a reasonable amount of work (1 hour a day) in Year 5 and Year 6. As our state primary school does not give much homework, this is very manageable. Children, who are not used to doing work regularly at home, will be more stressed if they are suddenly loaded up with tutors and work towards exam time, and this also emphasizes the fact that these exams are ‘super important’ which drives anxiety. If little and often has been part of life from the start, then exam preparation remains part of normal life and the attention and importance of exams (and therefore their outcomes) can be normalised.

- Let Life Go On:It is really important that children get selected into schools that are academically suited to them. If your child has extra-curricular activities that they enjoy as down-time, or that they would wish to continue in secondary school, then it is really important that these continue throughout the period approaching exams. If a child requires to stop everything else in their life in order to work towards exams, the likelihood is that they may be selected into a school where they cannot keep up with the class unless they continue to work at this heightened level. This leaves children in the stressful and vulnerable position of potentially giving up enjoyable extra-curricular activities forever. Extra-curricular activities are usually enjoyable and act as a source of stress release and social interaction. Some parents think that it is advantageous to ‘sneak’ spoon fed children into highly academic schools, but believe me, this is never advantageous. If children are unable to keep up they will be ‘managed out’ of these schools which can sometimes be ruthless about maintaining their league table status, and if a child has to work all-out to keep up, then this has consequences on their mental health.

- Realistic expectations and realistic explanations: I have a notion that self-awareness is the key to happiness. That if we understand ourselves and perform to our expectations then we are happy. Unhappiness arises when we do not know who we are or fail to live up to our own expectations of ourselves. This is of course more likely to happen if our expectations of ourselves are unrealistic. For many of us, myself included, I only truly felt that I started knowing who I was in my late twenties, and now in my forties, I am perfectly content with my own flawed self. Imperfect but comfortable in my imperfection – like an old pair of shoes. For the typical 11-year old child where identity is yet to be fully formed, ‘expectations’ are defined by parents. To prevent children feeling like they have fallen short, try to ensure that expectations are set at ‘realistic’. Asking school teachers, reviewing children’s independent work and having an idea of the academic level required for particular selective schools is important when choosing schools for your children. It is OK to be ambitious and choose some schools which may be a stretch, but if you are doing this, then explain it clearly to your child that there is no expectation to get into these schools, but that they are worth a punt. I take the school selection decision as a spread betting exercise and have opted for a selection of schools with varying academic vigour and will let fate decide. State school options are included in this spread bet and are talked up as being as appropriate as the private school options.

- Preparing for Failure:Children will always take things harder if they are not prepared. Many children, particularly the high-achieving and confident children that tend to apply for selective schools, have never experienced failure before. Make sure that failure is discussed openly well before exam time. Put your own failures on the table and demonstrate that failure is not something to be embarrassed about, but a normal part of life. Inculcate the mantras: “Strength is not in the never falling, but in the getting up after a fall.’ And “If you are not constantly failing, you are not really stretching yourself.” I will explain this latter statement. Children who participate in competitive sports will have a wealth of analogies that can be used to demonstrate this. Thankfully Molly does a spot of competitive swimming and is used to constant failure as the thing with swimming is that once you get to the top of a group, you get moved to the next group and start at the bottom again: succeed at school swimming, attend club swimming, succeed at club swimming, attend county swimming, succeed at county swimming, attend regional swimming and so on and so on. Unless you are Rebecca Adlington, somewhere along the line you will fail, fail, fail! What excellent life experience! I highly recommend this as an extra-curricular activity for acclimatising to failure! The truth is this: if you are succeeding easily constantly, your pond is too small. Of course, discussing failure openly can also bring up hiccups. During an explanation of why it was no problem not to get into the grammar school (before it actually happened), Molly pipes up: ‘You don’t think I’m going to get in do you?” – it’s always a good idea to answer these questions honestly: “You know what Molly? I think you have a good chance, but I really don’t know because there are a lot of other clever girls out there who all have a good chance. But it doesn’t matter if you don’t get in because it just means that the school is not suited to YOU, and there are other good schools that will be.”

- Contain your judgement.Children around this period are hawks to information and opinions about various schools. Much of it is hogwash because ‘one man’s beef is another man’s poison’. Literally. A highly-academic school can propel some girls to glittering careers, but the same school can contribute to a different girl to commit suicide. It’s all about ‘fit’. Therefore, it is no good listening to the judgements of other parents to make decisions about your own children, and its no good transferring judgements about schools to your children. They will take these comments from you as gospel and it will affect their mindset and they will tell their friends, spreading irrelevant judgements. Although I have chosen a variety of schools, I never talk of a preferred school and merely state that all of them are good. Other parents find this extremely frustration and keep pushing me with “But REALLY, which one is your preferred school?” and my honest-truth is REALLY– my preferred school is the one that offers a place to my daughter! It helps not to pay too much attention to the school propaganda machine and prospectuses which imply that they will be the only ones to hone and sculpt your child’s mind in the right way. In my opinion, there is no such thing as ‘one partner who was destined to be my lifelong love’ (sorry hubby) – there are many people in this world who we could each have fallen in love with; and equally there are many, many schools which will do a good job at educating my children. Unless you are an Oscar winning actor, if you have a ‘preferred school’ that you have singled out as being ‘the ONE’, it will be very difficult to hide disappointment from your children if they don’t get in. Anyone who has gone through the house buying process in the UK will have experience of the disappointment of being ‘gazumped out of our dream home’ and quickly realises that the scatter gun offering on many perfectly acceptable houses and THEN loving the one that you exchange on is a much better strategy.

Also – I am a control freak and if anyone is going to be ‘shaping my child’s mind and attitudes’ – it’s going to be ME! Mu ha ha ha ha. (For as long as possible anyway!)

- Contain your own anxiety. OK, I have to fess up that every 8-10 weeks I do have an anxiety wobbly where I worry that no selective school will take my money and accept my daughter to their school and that by some freak influx of 11 year olds to my local area, we will now live too far away to get into the good local state school. At least though, I recognise this anxiety wobbly for what it is and am able to mostly keep it to myself, give myself a good slap around the chops and saying: ‘stop catastrophising’. I doubt any parent can really get through this period without a stitch of worry and anxiety, but the best advice is to ‘Keep Calm and Carry On’ and preferably try not to show your anxiety to your children as your anxiety is fuel for their anxiety.

- Pride and unconditional love. If you are a bit shy about expressing your emotions to your children, now is a really good time to release yourself from your shackles. Go all out on expressing pride and unconditional love. This does not mean that you let children off the hard work that they are likely required to do, but that the effort that they put in is noted, praised and whole-heartedly appreciated, as well as their non-academic attributes that make them the lovable person they are.

- Silver Linings.When failure happens, make sure that you accept it. Highlight the silver linings to yourself and your child. It’s better that you actually BELIEVE these silver linings, other-wise your child will know that you are just trying to make them feel better and see it as fake. If you can, convince and accept it yourself first then you’ll be able to deliver the silver linings genuinely. You might feel some innate need to contest the failure and imagine some mistake has been made and feel a need to make an appeal. Alternatively, you might feel that it is necessary to make up an excuse as to why your child didn’t get in to a particular school or feel embarrassed to divulge failure to family and friends. All of these common parental behaviours meant to make your child feel better often have the paradoxical effect of making the failure hurt more for your child as they highlight your disappointment and disbelief in the legitimate outcome. As I said, unless you are an Oscar winning actor, try to be genuinely happy with the outcome as if you feel disappointed, your children will know about it however much you try to keep it from them. Many 10 year old children’s main wish is to make their parents proud. Conversely, feeling that you have made your parents ashamed or disappointed can feel like agony.

To all parents embarking on the same journey as me in the next 2 months:

Stay Sane!

To all girls and boys out there who are embarking on the same journey as Molly in the next 2 months.

Good Luck!

You will be Brilliant wherever you go to school!

Back to School

For many parents it’s back to school this week, a time of mixed emotions. I’m sure that I am not alone in feeling a sense of relief (thank God I’m no longer responsible for them 24/7 or for organising who will be responsible for them 24/7), sadness (how the heck did they get this big? A minute ago I was wiping their bottom) and anxiety (how will they get on with their new teacher?).

The “Back to School” prep has all been done. This year, thanks to a last minute job application form that was due, the majority was delegated to Banker. For the first time, he braved John Lewis alone with the kids to battle over the last Size 3 Geox, AND he ironed on all the name labels on the new uniforms. This latter he did correctly this time as last year when he was assigned this task he spent an hour ironing on sticker name labels (used for books and pencil cases etc) rather than the iron-on name labels (used for clothing). They obviously didn’t stick and I had an absolute barney as I had to repeat the task. This year all was done to standard, which goes to show that these parenting tasks need not be the preserve of mums (if we are happy to tolerate a hiccup or two)! All I did was get Lil Bro his back-to-school haircut and then they were set.

As soon as my kids saw their friends they were off without a backward glance.

I toddled off to the shops. It was with sadness that on my return from the shops, a good hour after the school bell had tolled that I saw a mum and her son outside the school gates. I heard a snapshot of their conversation “Just go in and talk to the others. It’ll be fine.” It occurred to me that for some families, “back-to-school” is not just a logistic nightmare of name labels, new shoes and haircuts, but a return to a battle-ground and heartache.

As an autism specialist, it is not uncommon for my clients to loathe school and in extremis to refuse to go to school. Anxiety is the most common co-morbidity in children with autism, and it is also the most common mental health problem in primary school aged children. So here are a few pointers on school refusal:

Try to find the cause for anxiety

- Encourage your child to feel safe to talk to you about their problems. This requires a non-judgemental attitude and a guarantee of confidence and that they will not get into trouble. They will also need to know that they will be taken seriously, and that you will have the resources and strength to help them. Many children I see in clinic do not disclose bullying to parents as “it will worry them”, “they won’t believe me”, “they will only confront the situation and make it worse” or “they won’t be able to do anything”.

- Often it is not sufficient to ask your child why they will not/ do not want to go to school. Persistent badgering on this question may cause more harm than good if it is not forthcoming given encouragement. Sometimes your child may not fully understand their own emotions or the cause of their emotions and therefore cannot tell you even if they wanted to. In this instance, it is up to you to speak to teachers and friends and come up with your best guesses. Discuss these hunches with your child in a non-judgemental way: “If I were in your shoes, I’d be a little scared of your new teacher…” and see whether any of them chime with your child. This is a favourite child psychiatrist strategy of mine as usually one of your guesses will be correct and when you see a child’s face respond to you verbalising their darkest emotions, you can tell that you’ve got to the heart of it and work can begin.

If you find a cause then dealing with the cause will be your next step. Some common causes for school refusal in primary aged children are:

- bullying/ social ostracisation by peers

- bullying/ fear of a teacher/ fear of being told off

- anxiety about a particular subject: fear of failure in an academic subject, fear of being ridiculed in P.E.

- anxiety about leaving the parent (separation anxiety) for fear something may happen to the parent.

Sometimes, there is no one-single cause and anxiety may be generalised or the sum of minor anxieties that can overwhelm. Working through each one, however minor, can be important.

Dealing with the cause should always involve:

- Working together with the school. The natural parental instinct is to do your utmost to protect your child which can mean confronting the school staff or the parents of other children. Try to stay calm and keep an even head – whatever happens, getting other parents and teachers on side will lead to better outcomes for your child than making adversaries.

- Supporting your child. As well as in relation to the identified cause, increasing your child’s self-esteem, resilience and social skills will always help.

Avoid pitfalls:

- Sometimes, parents will allow children to stay off school due to school refusal. It is important to remember that this can inadvertently encourage problems as you are in effect teaching your child that crying and fussing will lead to a day off school. Sometimes it is impossible to get a child into school, but if this is the case, then schoolwork should be done at home rather than a pleasurable day at home watching TV and playing computer games. An incredibly boring or taxing day of chores at home may lead some children to the conclusion that school is preferable!

- If at all possible, get children back into school as quickly as possible because the longer that they are off school, the harder it will be to get them back.

How family ski holiday hell can protect your child from perfectionism

Last week I was on the obligatory family ski holiday. Around this time of year, there is no getting away from it for those of us privileged enough to be in the demographic that “does ski holidays”. For most people, the dilemma is about “to dump” or “not dump” the children. Whizzing down black runs is not something one can achieve with a baby or toddler in tow. If your children are old enough to learn to ski, then “dumping” the children in ski school becomes legitimatised as “teaching your child a life skill”, a “healthy sporting activity” or for the tigers “brownie points for extra-curricular activity on the child’s CV”. There will be those who opt for all day children’s ski school and others who opt for ski resorts with all manner of childcare facilities so that they can get a good days skiing in. Reserve a place at the resort crèche where the children will participate in all manner of “arty-crafty activity” and they will mix with European children and might even learn a little French or German. Wunderbar! Hire a chalet nanny, or hell, bring your own nanny (or grandparents) with you. Why not? It’s your holiday as well right?

I have no problem with “dumping children”, but what I dislike is the pretence surrounding it. Why not just be honest and say “I love skiing and this is the one chance a year I get to do it”? If you are going to do it, indulge and do it guilt free. We all need a break sometimes. However, I would refrain from framing it in your mind as a “family holiday” and make sure you have a “proper” family holiday where you actually engage with your children as well. Even better, take turns with your spouse to go during term time without the children – they will feel less “dumped” that way. Given that most people that can afford extravagant ski holidays are also the ones working long hours and not spending quality time with their children, holiday contact is really important, and if the only holidays you have involve a crèche and a nanny then you have to begin to think about the impact of this on relationships with children. I opt for morning session ski school and family time in the afternoon. Banker is quite good at taking Lil Bro skiing between his legs and Big Sis can now ski independently. Banker says he gets great satisfaction watching the children’s skiing coming along. Haven’t I trained him well?

I have a different reason for finding family ski holidays a chore.

I don’t ski.

Not having grown-up wealthy, skiing every winter was not part of my childhood. By the time that I was earning enough money for ski holidays, I was spending my money on holidays to South Africa to visit Banker as we spent 3 years living in different continents and holidays were our only time together. By the time that we eventually managed to live in the same place, I was the lone “non-skiier” of my friends and I didn’t fancy being the hole in the donut of other people’s ski holidays.

I had happily been avoiding ski holidays to no great regret. “Oh no, I can’t come skiing, we are off to explore the temples at Angkor Watt”; “Oh, sorry, maybe next time, I’m off to climb the Himalayas”; until kids. Given that my kids are de facto wealthy by UK-not-London standards (Big Sis has proclaimed herself “Rich” – when I questioned this, she replied “I will be when you two die.” Typical Big Sis!) – was I going to stand in the way of their wealth-based leisure pursuits?

I have in mind independent secondary school and Russell Group University ski tours and ruddy faced chaps called Tristan and Hugo that might wish to invite Big Sis to a family ski holiday; or blond, horsey gals called Cressida that might require Lil Bro to deliver chocolates to her. Did I want to deprive them these opportunities?

So I have been forced onto the slopes against my will by my diligent parenting ethos. My ski instruction to date has so far consisted of 3 hours with a private ski instructor. Ski instructors are usually of the buff 20 year old variety so it is no great torture, particularly as I spent many parts of the 3 hours being hoisted and supported by them (“Oh dear, I’ve fallen down again!”). This time however, the private instructors were all fully booked so I was left to my own skill (or lack thereof) and my darling husband.

Think of the second Bridget Jones movie and you get the idea of how I spent the last week, only worse as frankly, Renee Zellwegger would look great in a paper bag. Think: short, Chinese person dressed head-to-toe in Decathalon with sporadic catalepsy. No button lift was able to keep me upright and even flat terrain was insufficient to guarantee that I could stand. There was the time that a failed turn left me skiing backwards for a time screeching like a banshee till I fell forwards and tried aimlessly to use my fingers to stop my downward trajectory so that I left a trail of scratch marks in the snow like a demented cat failing to cling on for dear life in a cartoon. There was the time my ample bottom fell off the miniscule button of the button lift, but fearing that I would be left alone half way up a mountain slope, I carried on holding on to the lift with my arms so that I was dragged on my backside for several metres before I decided I had better let go. Or the time that I fell over for no apparent reason whilst attempting to embark a button lift and couldn’t get back up and in a truly British way, not wanting to hold up the queue of teenagers waiting to get on the lift, I heroically gestured that they ought to “Don’t mind me” and encouraged them to just step over me in the interests of the queue. Speak nothing of the slope-side verbal exchanges with Banker, incredulous at my ineptitude when I tried to put my skis back on with my skis pointing downhill. Let’s just say that I measure the success of my skiing by the ability to descend a slope alive. If no bones have been broken, it has been a successful day.

Then there was the time that I hurtled down the piste, poles akimbo at constant risk of entanglement with my skis, ineffective snow plough engaged, heart and lungs in my throat, in perfect uncontrolled freefall, shouting “sorry” every 5 seconds as I cut across paths of furious proficient skiers and forcing snowboarders on their knees as they are forced to divert their course unexpectedly, as my life flashed before me. Only then to glance sideways to see Big Sis and an orderly row of bibbed midgets skiing calmly, gracefully and naturally down the slope past me.

Ah, it’s all worth it. Hope Cressida and Hugo will be thankful.

In hindsight though, I think there is a further benefit of my ineptitude. In this age of heightened perfectionism sending eating disorders and depression in children soaring, what better role model can there be for the nonsensicalness of it all than a parent who is prepared to put participation in front of looking good and doing well. For all the talk of promoting “non-competitive” competitive sports at school and inviting motivational speakers into schools to discuss successes that have come from failures, surely the most impact to children on this matter can come from parents who are not afraid to demonstrate failure and can wear it with a smile?

And I sure do epic fails and falls well!

Fear and Phobia in Children

It’s Halloween, so what better time to think about children’s fears? Clearly, for most kids, the idea of dressing up as a zombie, blood sucking vampire or evil witch is fun and funny, so what do children find frightening and why?

There is no easy answer to this, as you get some children with very strange fears (for instance I have met children who completely freak out at hairs in the bath or the texture of flour), but I will try and describe in general the progression of fears common to most children. Fears typically vary depending on age and intellectual capacity, moving from almost “instinctive fear” in babies to sophisticated fears of abstract concepts in adulthood, that require more elaborate thought processes.

For babies and toddlers, whose cognitive capacity is still basic, fear is more of an “instinct” than involving much active thought and cognition. Evolution has honed humans to have brains that are hardwired to fear certain things that have served our ancestors well in the past: for instance loud noises (which could have denoted a falling tree, an earthquake, a sabre toothed tiger or any manner of danger) and heights, which if not avoided could lead to untimely death. If you make a loud unexpected noise next to a baby, they will most certainly startle and most will start crying. So aversive are loud noises to babies that it is possible to induce a phobia in babies by using a loud noise.

A phobia is an extreme fear associated with an object or situation. Clinically speaking, it requires that the fear leads to avoidance of the object or situation causing disruption to a person’s day-to-day function. “Little Albert” is a classic case in the psychology literature of a phobia being induced in a baby using loud noise. Little Albert was a 9 month old boy who was not afraid of rats and was given a rat to play with. A dastardly psychologist John B. Watson wanted to see if it was possible to cause a phobia of rats. Every time little Albert touched the rat, a man stood behind him and banged a piece of metal with a hammer making a loud noise scaring little Albert. Needless to say, after a while of this, Albert became afraid of rats and stopped going near them, proving it is possible to induce a phobia. Thankfully ethics boards no longer allow this type of research.

Interestingly, there appears to be an evolutionarily hard-wired biological predisposition to phobia development to things which are traditionally harmful. Thus even in adults, it is easy to induce a phobia for things like rodents, snakes and spiders but very difficult to induce a phobia to cars, guns and knives which are more likely to be a real threat in the modern age.

Although it is hard to prove whether a fear of heights is innate in babies, supporting evidence comes from Eleanor Gibson’s visual cliff experiments of the 60s which tested 6-14 month old babies. Here babies were encouraged by their mothers to cross a floor that had a section partway made of transparent Perspex over a ditch. Most babies would not crawl over the Perspex even though they could feel the floor was solid with their hands. Some babies cried as they “could not” get to their mothers for fear of falling into a ditch. Some fearful babies that did not dare cross rolled onto the Perspex part by accident, good evidence that fear, does not necessarily prevent accidents and proving that babies should not be left near real cliff edges! A few other babies, whether due to fearlessness or ignorance crawled over the Perspex. The dumb and fearless – either bound for greatness or an early exit.

At this young age, babies (at least baby monkeys) are also primed to fear what others fear. This evolutionary trick allows babies to quickly pick up the dominant threats in its environment, as if others feared something; it would probably do them good to quickly learn to fear it too. Mineka showed this clearly in Rhesus monkeys who were laboratory raised and did not fear snakes. After showing the monkeys videos of wild monkeys showing extreme fear to snakes, the baby monkeys became afraid of toy snakes in the laboratory, despite never personally having had an unfortunate encounter with a snake. Babies and young children are also primed to attend to their parents’ fear. I acutely remember breast feeding Big Sis while watching a horror movie late one night. At one point, I held my breath in anticipation of something horrible happening on screen. It would have been imperceptible to most people as I did not move or make a sound, and yet, Big Sis stopped suckling, tensed and looked at me. She could not yet sit up, walk or speak, and yet, she could sense my “fear”.

As toddlers grow into infants, they begin to develop cognitively. With this comes the beginning of understanding about the world and of imagination. They can start thinking about things that could happen beyond their own direct experience. At this age “The dark” and “monsters” are quite common fears. Often the children’s fears are completely unrealistic and may come from the strangest of places. When I was a young child, I couldn’t sleep one night and walked downstairs to find my parents. They were watching “Jaws” and I walked in at the inopportune moment when someone got munched. For several nights after this, I had nightmares that “Jaws” would come through my bedroom window and munch me. My parents found this hilarious and at the time, I didn’t quite understand why. Recently, my own children’s fears have been a source of interest and amusement to me, although I try to take it seriously and not be amused in their presence. Big Sis, while having no problems with the Maidmashing and Bonecrunching giants when we read Roald Dahl’s “The BFG”, refused to continue with “Maltida”, for fear of Mrs Trunchbull. Several nights of sleep for Big Sis and disturbed evenings for us lay at the hand of Mrs Trunchbull. Lil Bro on the other hand, took grievance with Violet Beuregarde. For some reason, being turned into a blueberry was the stuff of nightmares. Her return to normality by means of juicing fuelled rather than quelled the fear.

At this age, what parents fear are real fears are often not well understood. The ever-present fear of parents: “How will my children cope if I die?” is not at all a concern for children at this young age. They neither comprehend death nor a realistic meaning of time. Once when I uttered out loud my fear of “What will happen to you children if I die?” to my chagrin, Big Sis with typical “matter-of-fact” style replied “Oh, it will be fine, we will still have Dad”. By the age of 5-8, however, children come to understand the meaning of death and fear of death becomes a common fear in this age group.

The middle childhood years (6-12 years), are also the peak age for acquiring fear of animals. Dogs and spiders are pretty common fears for children. Sometimes, a child will develop a fear because of a specific experience with an animal, but other times, they may have a fear even without a direct upsetting experience as evolution has predisposed our brains to accepting that animals are potentially dangerous. In reality, cars kill more people than animals, and yet, practically no one develops a phobia of getting into a car without a direct traumatic experience. As children reach adolescence, fears become more similar to the fears of adults: fear of failure, fear of humiliation, fear of rejection, fear of war, illness and crime come to the fore. Whilst on the one hand, these fears are more “realistic” than the “boogie man” fears of infancy, one can also make the argument that many adult fears are also unrealistic. Fears about an ebola outbreak in the UK are probably over and above the realistic risk.

It should be remembered that fear is a natural response and it helps to serve a vital function. Without fear, our species would likely not have survived, by putting ourselves in the direct line of danger without regard. The fear response allows not only the bodily preparedness to fight or flight, but also the brain response to pre-empt adversity, plan and avoid. People who show low levels of fear often show high levels of “risk-taking behaviour”, and often end up in trouble one way or another whether it is in a high-speed car accident, audacious robbery or in bringing down the banking sector. However, fears should be based in reality and the work of psychological treatment for anxieties and phobias includes anchoring fears in reality.

As a parent we cannot shield our children from all adversity and helping children to understand and deal with anxiety and fear is part of our role as parents. Teaching children to accept and have the confidence to know that they can handle fearful situations when they arise is more important than preventing fearful situations arising or promoting gung ho “bravery”. Security and reassurance is the key; but sometimes it is easier said than done.

When Big Sis was in Year 1, she studied Edward Jenner and small pox at school. The idea of small pox put the fright into Big Sis like nothing before. Not only was her sleep disturbed, but even in the day she would get tearful thinking about the family being killed by small pox. This went on for a week, and despite my reassurance that small pox no longer existed in England anymore, she was still tearful and upset. I eventually went to school to see her teacher to tell her of the situation. When I picked up Big Sis from school that day, she declared to me that she was no longer afraid of small pox.

“How come?” I asked having given reassurance all week to no avail

“Because the teacher told me about the small pox vaccine.”

“Er –haven’t I been telling you about that for the past week?”

“Yes, but you’re just mum, she is a TEACHER.”

Guess that medical degree doesn’t count when you are just a mother…

References:

Gibson, E. J., & Walk, R. D. (1960). The visual cliff. Scientific American, 202(4), 64−71.

Mineka, S., Davidson, M., Cook, M., & Keir, R. (1984). Observational conditioning of snake fear in rhesus monkeys. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 93, 355−372.

How anxiety in pregnancy can lead to anxious children

This is the last of the How to improve your child’s success before they are even born series. See Part 1, Part 2 and Part 3. OK, its pretty heavy going on the science, but if you really want to understand anxiety then its worth a read.

Most people are aware that stress and anxiety are not good for pregnant mothers. Even in 400 B.C., Hippocrates espoused the influence of emotions on pregnancy outcomes, leading to a plethora of literary dramas old and new where stress has caused the leading lady to miscarry or go into premature labour. More recently though, following Barker’s theories of foetal adaptation to the mother’s womb environment (see my post How to improve your child’s success before they are even born: Part 3), scientists have found that a mother’s anxiety in pregnancy can influence psychological and behavioural outcomes of her developing foetus over and above those caused by premature delivery. There is now a well-established literature base linking mother’s anxiety in pregnancy to several psychological and psychiatric outcomes in children, including: anxiety, attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), cognitive problems, changes in temperament, aggression, conduct problems and even schizophrenia (Beydoun & Saftlas, 2008; Talge et al. 2007; Van den Bergh et al., 2005).

Animals stressed in pregnancy give birth to anxious baby animals

The first evidence for this came from animal studies. Researchers found that rats and monkeys exposed to stress in pregnancy produced offspring that had long-term difficulties with attention, motor behaviour, aggression, memory and showed “hyper-vigilant behaviour” (Van den Bergh et al., 2005). Hyper-vigilant behaviour in animals is a proxy for human anxiety. It incorporates being alert to potential threat with corresponding changes in body systems to prepare to respond to threat. Think about how you would have felt travelling to work on the underground the day after the 7/7 London bombings of 2005, and this is probably a good picture of human “hyper-vigilant” state. Darting eyes on the look-out for suspicious bags with no owner, or people with over-sized back packs, slight tension in muscles, slightly increased heart rate and breathing rate, a little bit more perspiration than usual and if someone were to pop a balloon behind you, you’d probably have been ready to run. Hyper-vigilance is a good thing if you are in a stressful situation. It has served me well on many a walk home from the night-bus stop. If you are continually hyper-vigilant or hyper-vigilant in non-threatening situations like social situations or on aeroplanes; it can be very problematic and is called “anxiety”.

In animals it is easy to experiment and find out what is happening, you can wire animals up to measure muscle tension, heart rates and perspiration fairly unobtrusively. Even better, you can take blood samples and measure the levels of “stress hormone” cortisol. By doing these experiments, scientists have been studying the various effects of maternal stress on animal offspring and among several suspected effects, they have found pretty conclusively that in animals stress in pregnancy causes changes in the development of the foetal stress regulation system, the Hypothalamic-Pituitary-Axis (HPA) re-setting it to be on heightened alert.

How does the body deal with stress? What goes wrong to cause anxiety? – an analogy

What is the HPA-axis? The HPA axis is a collection of parts of the body that communicate by hormones to regulate certain bodily responses, including the stress response. In its function to regulate stress-response, it works pretty much like the emergency fire service. When you see a fire, you pick up the phone and dial 999. This puts you through to a national call centre, where you are asked which emergency service you would like. Once they realise that it is the fire service you need, they contact the regional fire control centre which contacts your local fire brigade which sends out an engine to where you are. The firemen hopefully put out the fire and call back the fire brigade centre to report that the job is done, which then feeds this information back regionally so that the case can be closed. Alternatively, if the fire has gotten out of hand, they can report regionally or nationally depending on the extent of the fire to request more engines to help.

The hypothalamus (a region in the brain) is the national call centre. When the eyes see threat, they alert the hypothalamus. This lets the brain’s pituitary gland, (regional fire control centre) know that there is a threat and a stress response is required. The pituitary communicates with the kidneys (local fire brigade), which then provides the stress response: the steroid hormone cortisol (fire engine). The fire engine goes out to sort the problem. Cortisol does this by going to the heart and making it pump harder, it goes to the lungs and makes it breathe quicker, it goes to the sweat glands and makes them produce sweat, it goes to the muscles and makes them tense and ready for action. All so that you can either fight or flee the threat.

If a city undergoes a heat wave and there is an increased propensity to fires starting and burning out of control. The fire service would probably request more resources on standby and be on heightened alert to send out more engines. More engines than needed might be sent out to small fires to ensure that they did not catch and turn into large fires. This is precautionary and helpful in the short term, but is an over-reaction if continued long term, beyond the time of realistic threat. The same thing happens to our body’s emergency response system. If there is a history of heightened stress, the body responds by increasing the base level of cortisol in the blood stream and increasing the amount of cortisol released in response to stress. This is not a problem if there is continued threat, but if the situation calms down and the body does not down regulate its stress-response system, the result is persistent anxiety.

In animals at least, it has been shown that the animals themselves do not need to have been exposed to stress for their bodies to be placed on heightened alert, they merely have to be exposed to their mother’s heightened alert system in the womb. Thus in animal experiments, giving pregnant mothers injections of cortisol equivalent substances can cause their children to have higher base levels of cortisol and heightened cortisol response when they are born and with continued effect into adult life (Van den Bergh et al., 2005). These animals went on to display a range of long-term behavioural and cognitive impairments. This can be thought of as part of Barker’s hypothesized foetal programming whereby the foetus exposed to high levels of maternal stress hormone predicts a hostile environment and prepares itself by adapting its HPA-axis to best cope with impending fight for survival. Where the resulting environment is actually not that stressful; the HPA-axis is now not working properly and leads to a range of problems.

Who cares about animals? What about humans?

Stressing humans to study anxiety is rather unethical. Shockingly, it used to be allowed and “Little Albert” is a classic case in psychology literature. Little Albert was a 9 month old boy who was not afraid of rats and was given a rat to play with. A dastardly psychologist John B. Watson wanted to see if it was possible to cause a phobia of rats. Every time little Albert touched the rat, a man stood behind him and banged a piece of metal with a hammer making a loud noise scaring little Albert. Needless to say, after a while of this, Albert became afraid of rats and stopped going near them, proving it is possible to induce a phobia[1]. No wonder experimental psychology has a bad name!

These days, we are thankfully not allowed to do such things, but it does mean that extrapolating work from animal studies into humans is harder. We have to rely on stress that occurs naturally in the lives of pregnant women rather than purposefully causing stress in order to study its effects on offspring. Natural and man-made disasters have been used to study the effects of anxiety in pregnancy.

Studies of children who were in the womb of mothers affected by 9/11 showed that these children were born with lower birth weights even though they were born at term, compared to children conceived following 9/11 (Berkowitz et al., 2003). Infants whose mothers were pregnant during the 1998 Canadian ice storm that led to electricity and water shortages for up to 5 weeks scored lower on mental development indices and tests of language development compared to other children, even after taking into account birth complications, birth weight, prematurity and post-natal depression (La Plante et al., 2004).

It is not just extreme stress such as a national disaster that can cause effects. Studies have also used questionnaires asking pregnant mothers about their levels of stress at varying times in their pregnancy and then studied their children at varying ages from newborn to adolescence. In general the link between maternal stress and impaired offspring outcome is borne out, sometimes even with a direct dose-response effect[2] (Beydoun & Saftlas, 2008; Talge et al. 2007; Van den Bergh et al., 2005). Results from different studies vary as each study is different in terms of the stress they are measuring (some studies ask for work stress, bereavement, marital stress, criticism from partners, or just how anxious you feel), the time in pregnancy the stress occurs (studies vary in studying stress in the first, second or third trimester), and the outcome and age of children they are studying (some studies look at language and development in the first year, others look at ADHD symptoms in childhood and yet others look for anxiety and conduct problems in adolescence). Despite this, the majority consensus of all the studies is that there is a significant negative effect of maternal pre-natal anxiety which can have lasting effect. In this way, it is not just your DNA that is biologically influencing your child’s outcome, but environment, via biological mechanisms.This is epigenetics, the new buzz in child psychiatry research.

Interesting finer details

The theory regarding differences in timing effects is that this relates to timing of brain development. Throughout pregnancy the developing foetal brain goes from a neural tube to a baby’s brain which is a complicated journey. Different parts of the brain are forming throughout the 40 weeks, and the effects of insult to the brain at a particular period in pregnancy will depend on the part of the brain that is forming at that time. So for instance, a brain insult (such as anxiety) occurring at the time that the language centres in the brain are forming may lead to language deficits down the line. It is known that the links between pre-natal anxiety and schizophrenia are related only to stress that occurs in the first trimester (Khashan et al., 2008), whilst maternal anxiety experienced in the third trimester is more likely to cause offspring anxiety (O’Connor et al., 2002). Even more interestingly, there appear to be differential effects depending on the gender of the developing foetus, females more likely to develop anxiety, males more likely to be affected by attention, cognitive problems and aggressive tendencies! There is strong evidence for this in animal models and supportive evidence for this from human studies (Glover 2011; Glover & Hill, 2012)

The reason for these different gender outcomes has been thought about from an evolutionary perspective. Historically the female role in species survival in animals and humans has been to bear children and look after them, the male role has been to protect and provide resources. Different skills are required for these different roles. Thus, in a hostile environment, it pays for the mother to be fertile to ensure succession and hyper-vigilant to prey and threat. It pays for the father to go and explore new territory for food and shelter, to take risks to achieve this and to be aggressive enough to fight others for territory and food. In this context, the effect of stress in generating anxiety in females and cognitive impairment and aggression in males can be understood. Hey, in an Armageddon situation I think we would all want rough and tough Bruce Willis at our side not intellectual Stephen Fry.

In animal models it has also been found that stressed out female rats reach sexual maturity earlier, are sexually active earlier, have more offspring but invest less time in the care of each (Meaney, 2007). We have to remember we are talking about rats here, but in humans there is evidence that a harsh early environment (poverty, neglect, abuse) can lead to precocious puberty. You can draw any other rat-human parallels yourself.

The astute amongst you, might be complaining that this is all hogwash and that so many things might be confounding the picture. A confounder is something that can be related to both the purported cause and the outcome. The main ones affecting our current scenario are things like poverty, post-natal depression and maternal educational level. One could argue that a deprived, uneducated mother prone to depression is more likely to experience stress during pregnancy and more likely to have difficulty raising children, thereby causing the psychological deficits seen in their offspring in childhood and adolescence. In animal studies, this is easy to exclude, the new born pups or monkeys are cross fostered so that the mother stressed in pregnancy is replaced once the baby is born by an unstressed mother. Results remain. It is not possible to do this with humans.

In the majority of human studies, known and suspected confounders (social class, post-natal depression, maternal education to name a few) were measured and significant results remained even when these confounders were taken into account. What about the effect of genetics? It is possible to argue that a mother genetically predisposed to anxiety is likely to be anxious in pregnancy and to pass on anxiety genes thereby causing offspring to be anxious. You can see how hard it is to prove anything in science, yet clever research designs continue to come up to try and get to the answers. In a master-stroke of research design now possible due to the frequency of in-vitro fertilisation, Rice (2010) compared, in a cohort of IVF children, the association between prenatal stress and child outcome in those who were genetically related to the mother with those who were not (i.e. receiving egg donation). They found there was an association between mother’s stress in pregnancy and child’s symptoms of anxiety and conduct disorder even in the unrelated mothers.

How does this relate to you and me?

So, how to prevent anxiety in pregnancy? For me, I was smug reaching pregnancy having achieved a stable, loving relationship, stable financial and employment situation and having lived child-free life to the full. I felt I was ready to face pregnancy and motherhood in the best position that I could be in to avoid anxiety. There would have been nothing to stop a loved one being run over by a bus or being faced with infertility problems or illness but, at least the readily controllable variables were answered for.

Things can’t always go as planned though! Typical of most pregnant ladies, the thought of a new bald addition to the family somehow provokes the mental image of bald addition being placed into a beautiful, white cot with pressed linen sheets in a light and bright nursery attached to a south-facing home with wooden floors, modern furniture and period features. Hence in the first trimester of pregnancy Banker and I embarked on a 10 month process of flat hunting, flat offers, flat rejections, flat offer accepted, flat exchange of contracts, flat completion delay, eviction from rental and 2 weeks of homelessness, worldly goods in storage and 2 week enforced holiday in France to avoid sleeping on the street, flat completion, moving in, moving out, flat total remodelling and renovation, all of which no doubt sent the cortisol flying through my placenta!

Here biology and scientific literature come to the rescue again. Thankfully, like all natural miracles, the pregnant body seems to do all it can to protect itself and its prize. It is well known that in the third trimester of pregnancy and for a period post-natally the body dumbs itself right down (Henry & Rendell, 2007). Having for many years prized myself on my amazing memory and lauded it over my husband who seems to have been born with the happy disposition of the forgetful, I became just the same. Misplacing things left, right and centre, but instead of fretting and panicking, just sitting back and saying “Ah, sod it”. During my last week at work, I merrily typed away at a patient’s report only to re-read it to find that it was gobbledegook! Evolutionarily this dumbing down particularly affecting memory impairment is likely to protect against the harmful effects of third trimester anxiety, as well as to help block out the trauma of childbirth so that we become willing victims for another round!

Further, there was a caveat in the maternal anxiety literature! In a review of the literature, Vivette Glover (2011), a fellow North West London resident, describes studies selecting only well-off middle to upper class women in stable circumstances. They found that in this group mild stress in pregnancy had a beneficial influence on child outcome with better mental and physical development of the children and a similar trend for IQ. The suggestion is that in this group of women, a small amount of pre-natal stress may actually enhance foetal brain development. This inverted-U shaped dose-response effect is typical of anxiety and you will be familiar with the idea that a small amount of anxiety helps you sharpen your attention to perform on stage or in an exam, but too much anxiety can cripple your efforts. If Big Sis wins the Nobel Prize, I’ll be remembering to send a bottle of bubbly to my builders for the aptly timed “mild” stress!

References and Influences:

Beydoun H, Saftlas AF. Physical and mental health outcomes of prenatal maternal stress in human and animal studies: a review of recent evidence (2008). Paediatric and Perinatal Epidemiology, 22, 438–466.

Talge, N.M., Neal, C., Glover, V. and the Early Stress, Translational Research and Prevention Science Network: Fetal and Neonatal Experience on Child and Adolescent Mental Health (2007). Antenatal maternal stress and long-term effects on child neurodevelopment: how and why? Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 48, 245–261.

Van den Bergh, B.R.H., Mulder, E.J.H., Mennesa, M. & Glover, V. (2005). Antenatal maternal anxiety and stress and the neurobehavioural development of the fetus and child: links and possible mechanisms. A review. Neuroscience and Biobehavioral Reviews, 29, 237–258.

Berkowitz, G.S., Wolff, M.S., Janevic, T.M., Holzman,I.R., Yehuda, R., & Landrigan, P.J. (2003). The World Trade Center disaster and intrauterine growth restriction. Journal of the American Medical Association, 290, 595–596.

LaPlante, D. P., Barr, R.G., Brunet, A., Du Fort, G.G., Meaney, M.J., Saucier, J.F., Zelazo, P.R., & King, S. (2004). Stress during pregnancy affects general intellectual and language functioning in human toddlers. Pediatric Research, 56, 400–410.

Khashan, A.S., Abel, K.M., McNamee, R., Pedersen, M.G.,Webb, R.T., Baker, P.N., et al. (2008). Higher risk of offspring schizophrenia following antenatal maternal exposure to severe adverse life events. Archives of General Psychiatry, 65, 146–152.

O’Connor, T.G., Heron, J., Golding, J., Beveridge, M., & Glover, V. (2002b). Maternal antenatal anxiety and children’s behavioural/emotional problems at 4 years. Report from the Avon Longitudinal Study of Parents and Children. British Journal of Psychiatry, 180, 502–508.

Glover, V. (2011). Annual Research Review: Prenatal stress and the origins of psychopathology: an evolutionary perspective. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry 52, p 356–367.

Glover, V. & Hill, J. (2012). Sex differences in the programming effects of prenatal stress on psychopathology and stress responses: An evolutionary perspective. Physiology & Behavior 106 (2012) 736–740.

Meaney, M.J. (2007). Environmental programming of phenotypic diversity in female reproductive strategies. Advances in Genetics, 59, 173–215.

Rice, F., Harold, G.T., Boivin, J., van den Bree, M., Hay, D.F., & Thapar, A. (2010). The links between prenatal stress and offspring development and psychopathology: Disentangling environmental and inherited influences. Psychological Medicine, 40, 335–345.

Henry, J.D. & Rendell, P.G. (2007). A review of the impact of pregnancy on memory function. Journal of clinical and experimental neuropsychology, 29 (8), 793–803.

[1] Interestingly, there appears to be an evolutionarily hard-wired biological predisposition to phobia development to things which are traditionally harmful. Thus, it is easy to induce a phobia for things like rodents, snakes and spiders but very difficult to induce a phobia to cars, guns and knives which are more likely to be a threat in the modern age.

[2] A dose-response effect is an effect whereby the greater dose of something purported to cause a particular effect, will cause a greater effect. For example, if sun exposure is linked to tanned skin, a dose response effect would mean that more sun exposure leads to a deeper tan. Finding a dose-response effect is good (but not necessarily definitive) evidence that a causal link exists.