Tagged: skin colour

My Chinese daughter thinks she’s a blonde

Race and skin colour is a tricky thing to talk about with kids, even in London where probably all 110 Pantone skin shades (yes this actually exists) are covered. I had my own (albeit mild) experiences of racism as an immigrant to the UK, and my fair share of ponderings regarding racial identity. I wanted my children to avoid that if possible, and thought I knew how to facilitate that. As with all things with children, things don’t always turn out as you plan!

It is natural that any parent uses their own experiences of childhood as a point of reference in parenting, both in how to do things and how not to do things. Having emigrated from Taiwan to the UK with my family at the age of 3 years, my race had at times been an issue for me growing up. It is well known that immigration has strong associations with mental health due to the stress both of leaving behind a social network and of feeling like an outsider, or “not belonging/ being accepted” in the new country. The stress of leaving behind family was more of a problem for my parents, but I certainly sometimes experienced the “not belonging/ being accepted” feelings. Although I was largely Anglicised; my outward appearance was clearly Chinese and this bothered me for a long time. I remember one instance when I was ten; I closed my eyes tight and wished very hard that when I opened my eyes again, I would have white skin. I didn’t want to change who I was, or my family, just the colour of my skin. It wasn’t the taunts of “Ching Chong Chinaman” or mock martial arts moves, which were easily dispelled by sharp tongue, but the pervasive stereotyping. Rightly or wrongly, I felt it was grossly unfair that all “Chinese people” (which actually included any East Asian ethnicity) were regarded as what I referred to as “book nerds”. Every teacher and every employer I have ever had has described me as “conscientious”. Why not “efficient”, “competent” or indeed “supremely talented” (ha ha) – which imply the same without the connotations of hard-working?

Because: only white kids were “naturally clever”, Chinese kids “worked hard, did nothing but work and were definitely uncool”…hmmm.

It’s definitely better now than in the past. Susie Bubble, Jemma Chan, Alexa Chung, Gok Kwan, Mylene Klass, Lucy Lui, Devon Aoki and even my old friend Ching He Huang are regularly on T.V. rocking the Asian cool. I don’t think that I would have had such an issue with being “Chinese” if I was growing up in London today, but I grew up in the era where Chinese people on T.V. were represented by Peter Sellers in fancy dress. An Indian friend described a similar stereotyping problem saying how “Indiana Jones and the Temple of Doom” was his most hated film, as he was forever being mocked about eating monkeys’ heads at his school, Eton. Funnily enough, it was also in the most privileged of environments, Cambridge University, where I experienced the most ignorant petty racial stereotyping. Frequently people commented on how good my English was and questioned where my Chinese accent was from, to which I responded “Norf London”. Others commented on my keenness for shepherd’s pie, remarking “I thought Chinese people only liked rice”. I am seriously not making this up! My poor Etonian friend fared no better. He went back-packing around Nepal with his friend, and on return was told by his friend that his family had mistaken him in the photos of the trip for “the hired native that carried the bags”.

I remember being acutely jealous of a Romanian friend of mine, who despite also being an immigrant to the country managed to pass herself off as the quintessential English rose by virtue of white skin, blonde hair and European name. She was never asked about Romania, Communism, “Why her English was so good?” or treated to random stories about “I met a Romanian once…”, unless she brought it up herself. It struck me that skin colour is important here, as whilst second generation Eastern European immigrants could be fully accepted as British, my children and grandchildren may not.

This thought was on my mind at the point of naming Big Sis and Lil Bro. I was acutely conscious that I wanted to give them the gift of racial anonymity. Being mixed race, they are a skin colour of “ambiguous” ethnicity. I wanted them to be taken for who they were, not what their name or skin colour represented. They were given mainstream European names and took my husband’s European surname, such that unless they chose to divulge their Chinese middle names, on paper, no one would be able to tell that they were not fully European. This was a fully conscious decision, because even though we live in much enlightened times, even in a cosmopolitan city like London, I think race and skin colour still mean something.

That said; I take instilling cultural pride and identity seriously. I definitely don’t want them to pretend that they are “European” and reject their cultural identity. They need to be proud of who they are and where they come from. My children are dutifully sent to mandarin classes to learn the language and culture, despite my own poor grasp of the language. My children are told that they are Taiwanese, and pitch up proudly on cultural days at school in Chinese costumes and brandishing the Taiwanese flag. They regularly eat Chinese food, they have visited Taiwan and spend regular time with their Taiwanese grandparents in London. They identify with being Chinese and in fact, when asked “Where are you from?” Lil Bro will declare he is “Chinese”, whilst the better informed Big Sis will explain how she is “From Taiwan, South Africa and England”.

Great hey? My plan was working. Strong knowledge, awareness and pride in ethnic roots and identity, but not being judged on ethnicity from the outset.

What happened next, was rather unexpected then.

It started with a discussion of Disney Princesses:

Me: Which is your favourite Disney Princess?

Big Sis: Sleeping Beauty. Or maybe Cinderella. They are the prettiest.

Me: I like Jasmine.

Big Sis: I don’t like Jasmine.

Me: Why?

Big Sis: She wears trousers.

Me [Phew, this is related to fashion rather than race]: OK, then, what about Mulan, you look most like Mulan.

Big Sis: No I don’t.

Me: Yes you do.

Big Sis: No I don’t.

Me: You have black hair and so does Mulan.

Big Sis: No I don’t, I have yellow hair.

This wasn’t a one off; this sort of thing continued. At the end of Reception, Big Sis’s Year 6 partner gave her a Chinese looking Barbie doll.

Me: That’s nice; she’s given you a Chinese Barbie.

Big Sis: How did she know I was Chinese?

Me: Because you look Chinese.

Big Sis: No I don’t.

Me: You have black hair.

Big Sis: No I don’t.

Me: You have yellowish, brownish skin.

Big Sis: No I don’t, I have light skin.

Me [What the hell?]: silence.

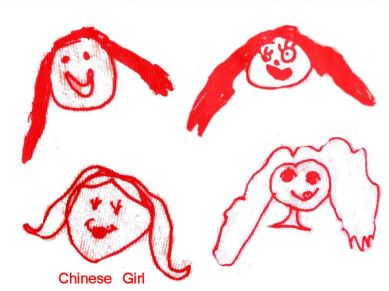

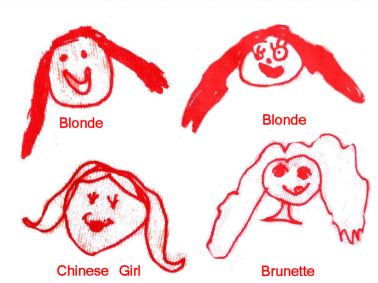

It was not a surprise then that when I bought Big Sis’s Year 1 tea towel with each child in her class’s self-portraits printed on it that I saw that she had depicted herself with “yellow” hair. What I didn’t expect and was relieved to see was that her blonde best friends, drew themselves with black hair, and another European child with dark brown hair also drew herself with “yellow” hair.

Maybe this is not about race then, but something deeper about identity and about wanting to belong. Wanting to be the same as your friends. It struck me that I could learn from this, that difference is in the eye of the beholder and where we seek to find similarity not difference, we can find it – however improbable.